Words by Mr Justin Quirk

Nike Pegasus Original, 1983. Photograph courtesy of Nike

Ihave been very particular about sneakers from as early as I can remember. My long-suffering mother would be dragged around endless shops on my Goldilocks-like quest for the pair that were just so. The most alluring of these locations was Cobra Sports, a now largely forgotten independent store that predated much of what is now commonplace in sports retail by some 20 years. The long, narrow shop off Kingston Market was crammed full of exotic shoes and labels, apparel that nowhere else stocked and, twice a year, sale bins, which I would descend on to find the perfect pair of trainers to last me for the next six months.

Shop the Nike Running collection here

My requirements were precise. They had to be from Nike (the brand’s glorious advertising, coupled with the endorsements of Messrs Ian Rush, Steve Cram and Steve Ovett reeled me in early), they had to be versatile enough to withstand everything from cross country runs to playground football sessions and they had to be priced so that my mother could afford them. I was 10 when I finally lighted on the perfect, all-round pair: the Nike Air Pegasus.

It was the start of a relationship that, on and off, has persisted for more than three decades. And it seems I’m not the only one. “I always worked in sports shops and whenever anyone was learning to run, the shoe you directed them towards was the Pegasus,” says Mr Brad Farrant, founder of sportswear distributor Make Room, sneaker collector turned marathon runner and avowed Pegasus fan. “That was the shoe that you got them to run in.” As I write this, a pair sit by my back door, drying out after a 15km run.

The Pegasus is Nike’s best selling running shoe of all time and has been a fixture of its catalogue for longer than any other model. First launched in 1983, priced $50, it was a response to the jogging boom, along with the Saucony Jazz and Puma Easy Rider. Originally conceived by Nike’s director of design concepts and engineering, Mr Mark Parker (with input from Mr Bruce Kilgore, who was then working on the Air Force 1), the shoe was intended to serve as broad a range of runners as possible, honouring co-founder Mr Bill Bowerman’s maxim that “if you have a body, you’re an athlete”.

The shoe evolved the design of the Tailwind, Nike’s first Air-cushioned shoe, with a small Air Wedge in the heel (most runners land on their heels, so the technology was needed only in the rear half of the shoe). “The name Pegasus stems from Nike’s beginnings,” says Ms Rachel Bull, senior product director of running at Nike. “It’s symbolic of our Greek heritage, named after the majestic, winged horse. Pegasus was intended to represent movement, quickness and the allure of flying on Air. Just as the Greek Pegasus was half horse, the Nike Pegasus was designed to be half Air.”

Find out more about the Nike Tailwind here

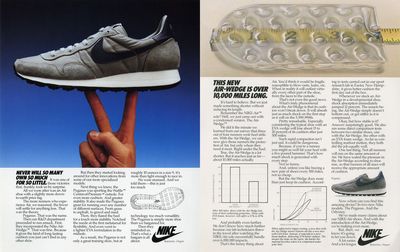

Nike Pegasus advertisement, 1983. Photograph courtesy of Nike

Despite this innovative use of the latest technology, the Pegasus always embodied a certain unflashy simplicity. As Mr Sam Grawe recounts in Phaidon’s new Nike monograph, Better Is Temporary, “While other shoes in the line may have offered greater stability or more cushioning, or have been more lightweight, the Pegasus came in just behind the leader in each category, making it the go-to selection for people just getting into sport or for serious runners in search of a practical training shoe.” Sneaker consultant, historian and long-time collector Mr Kish Kash concurs. “It’s Nike’s staple runner,” he says. “It’s the most accessible that Nike has. It’s just a great all-rounder.” As Ms Bull says, “We have dubbed it the workhorse with wings.”

Early advertising made much of the innovation that had gone into the Pegasus. Bar charts detailed the lifespan of the Air Wedge while the copy explained how heel flare improved stability. But in some fundamental way, the Pegasus was a utilitarian, functional, value-for-money shoe, as its first advert acknowledged: “Never will so many own so much for so little”.

Through the 1980s, as the public’s attention moved towards shoes with radical finishes (Nike Vandal Supreme), celebrity endorsement (Air Jordan) or more visible innovation (Air Max), the Pegasus maintained a workaday quality and a corresponding price point. Mr Grawe writes of how throughout its lifetime, the Pegasus has thrived by “mining insights from the leading edge of the company’s R&D and translating them into a shoe for everyday use”. In 1987, the volume of Air in the heel was quietly increased to give it twice as much cushioning as the Air Max (the Pegasus also became the Air Pegasus that year in recognition of its improved buoyancy).

Over the following years, while sneaker culture embraced everything from Pump technology to innovative fastening systems, the Pegasus evolved at a stately pace. Fabrics improved, cushioning shifted in line with the latest research, colourways broadened, but its profile stayed broadly the same. Compared with 1983’s model, the Pegasus ’89 had a slightly higher heel-to-toe drop, its sole components were divided vertically rather than laterally and it had an additional heel support, but the shoe basically looked the same. By the Pegasus ’92, the sole unit had gained an additional component, but it was still a standard, neutral running shoe.

Other shoes with sporting origins had been retired, but the Pegasus’s small improvements meant it endured as a performance shoe. The Cortez (“the supreme training shoe for the long-distance runner”, as its adverts boasted) had been superseded technologically. The Air Max was on the way to becoming a street shoe, not a runner. Key athletic styles from other brands, such as adidas’s Stan Smith and the Reebok Classic, couldn’t keep pace with modernity and migrated from performance to leisure shoes.

“In 1987, the volume of Air in the heel was quietly increased to give it twice as much cushioning as the Air Max”

The Pegasus dug in and carried on, year after year, mile after mile. About 17 million pairs were sold in its first decade. An apt comparison can be found outside sport. “If you think about the Volkswagen Golf, it’s been in existence since 1974 and it’s been through various iterations,” says Dr Thomas Turner, sports shoe historian and author of The Sports Shoe: A History From Field To Fashion. “And each time it’s been incrementally improved, but it’s remained identifiably a Golf. You can see the heritage and the lineage of it as it progresses through the years. It’s designed originally just as being a very good family car, and it’s remained true to that objective.”

It was only in the late 1990s that the Pegasus stumbled. Dropped from the line briefly in 1997, it suffered a few false starts on relaunch in the early 2000s, working through versions that were by turns bulbous, cluttered, frequently finished in reflective silver and apparently unclear of the shoe’s identity or heritage.

The shoe regained its footing in 2012 with the Pegasus 29, a sleek model that came in retina-searing neon tones, mirroring the colourways showcased by middle-distance runners at that year’s London Olympics. With a mesh upper, extraneous weight was stripped away while the stability of the shoe was maintained via printed overlays at key structural points. “We’re talking about engineering the upper to work with how your body is working within the shoe,” said senior footwear designer Mr Mark Milner on its launch. It remains a benchmark in modern running.

Since then, the Pegasus has enjoyed marginal gains each year, an almost perversely slow and steady, minimal approach to design in the face of the innovation arms race consuming running. Flywire lacing systems have come and gone, Flyease technology has been imported from basketball, eyelets have shifted slightly and in 2018 a full-length articulated Zoom Airbag appeared, inspired by the carbon plate that runs through the length of the record-destroying Zoom Vaporfly 4%’s sole.

The proof of the Pegasus’s quality has been in its near-constant appearance on the feet of the most demanding runners. “I’ve always been a simple guy. I wear the Nike Pegasus,” said Sir Mo Farah in a 2017 Nike video. “The Pegasus has been good to me.” The world’s only sub-two-hour marathon runner, Mr Eliud Kipchoge, trains in them, as does American mile record holder Mr Bernard Lagat, world 1,500m champion Mr Timothy Cheruiyot and current New York City Marathon gold medallist Mr Geoffrey Kamworor.

Sir Mo Farah wearing Nike Air Pegasus, 2013. Photograph courtesy of Nike

Mr Cory Wharton-Malcolm, founder of Track Mafia, a head running coach at Nike and Runners World columnist says, “When Nike discontinued the Flyknit Lunar 3, I was looking for another shoe that I could just throw on and enjoy running any distance in, just enough support and spring for anything. I’ve run fast 5ks in them and very chilled marathons in them. They are a workhorse.” Mr Andre Coggins, Track Mafia coach and founder of the Mafia Moves running crew, describes the Pegasus as “durable, affordable and reliable to most OGs in the running scene. The reliability of the Pegasus throughout training is so simple but effective and does exactly what it is meant to do for a runner.”

For a sneaker rooted in the culture of a previous generation, the loyalty and recognition that the Pegasus still generates is a testament to the mindset that existed within Nike at the time. “One of the things that is striking is that people were doing jobs that you wouldn’t necessarily have expected,” says Dr Turner. “They employed people who’d trained as furniture designers or industrial designers. They’re looking at this wider world of a much greater range of influences, so their shoes take on this element of being more than just well-designed products.”

As I have gone out running throughout lockdown, the dependability of the Pegasus has come into its own. Day in, day out, I find myself relying on what Nike originally conceived as the “shoe for every runner”.

During another long late-night run on my familiar circuit along the Thames, it occurred to me that we frequently think the wrong way about what runners want. The language and marketing around running is all about freedom and possibility, but we runners approach the sport in terms of structure, routine, data and repetition.

“Running is a sport of paranoia,” says Mr Farrant. “Even before you go running, every day you have the same thing to eat, you wear the same thing. It’s such an OCD sport. And I think you find with runners that part of the disorder is that they’ll always want to wear the same stuff. I suppose that’s why it’s always been in the Nike line, because people want to go with what they trust.”

In some ways, the Pegasus is the ultimate physical embodiment of this mindset. Runners, by nature, are not flashy or adventurous people. We push forwards incrementally, gradually increasing distance, testing our limits, edging our distance up and down as we build up our reserves. And the Pegasus has grown in the same way. This is what has given it such longevity.

Wherever you are in the world, as you read this, somewhere close by a runner will be striking out in a pair of shoes that are sober, unsurprising, somewhat boring – and completely irreplaceable. Long may they continue to be so.